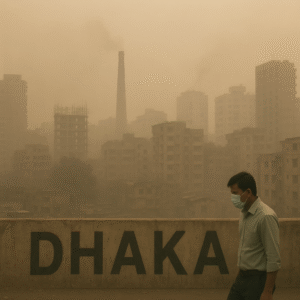

Deadly Air: How Dhaka’s Air is Slowly Killing Its People

Deadly Air: How Dhaka’s Air is Slowly Killing Its People

Every breath in Dhaka feels heavy, like an invisible weight pressing down on millions of people. The city’s air has become dangerously polluted, and the problem is growing worse every year. In early January 2025, Dhaka experienced its worst air quality in nine years, with the Air Quality Index (AQI) peaking at 318—a staggering 24.5% increase compared to previous winter averages. This level is classified as hazardous, making it unsafe for anyone to spend time outside without protective measures. Although summer months bring some relief, daily PM2.5 levels still average around 18 to 19 micrograms per cubic meter whereas World Health Organization’s (WHO) safe guideline for PM2.5 level is 5 micrograms per cubic meter.

Bangladesh as a whole continues to struggle with severe air pollution. In 2024, it was ranked the second most polluted country in the world, with an average PM2.5 concentration of 78 micrograms per cubic meter—more than 15 times the WHO’s recommended safe limit. Dhaka itself was the third most polluted capital city globally and ranked 24th among all major cities worldwide for its air quality. These rankings underline the critical air pollution crisis facing the capital and the nation. Despite some seasonal variation, the trend shows that pollution levels are rising and causing grave health and economic consequences.

The impact of this polluted air on human health is devastating. Fine particles like PM2.5 can penetrate deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream. They are linked to respiratory illnesses such as asthma and bronchitis, cardiovascular diseases, strokes, lung cancer, and an increased risk of mental health issues like depression. Each year, more than 1 lakh people in Bangladesh die prematurely due to air pollution. The number is especially heartbreaking when considering the toll on children: over 900,000 preterm births and nearly 700,000 infants with low birth weight have been linked to polluted air. Emergency hospital visits related to pollution reach over 670,000 annually. This not only causes pain and suffering for families but also creates a heavy burden on the economy, costing nearly 5 percent of the country’s GDP.

“Whether We Smoke or Not,

the Air We Breathe Today Harms Us All Equally.”

Several major sources contribute to the deadly air in Dhaka. Around 2,295 brick kilns operate in the region, many of which use inefficient and outdated technology. These kilns contribute between 40 and 58 percent of the city’s PM2.5 during peak months, especially in winter. The fuel burned in these kilns is often coal or wood, producing thick smoke and harmful pollutants. Additionally, the city’s rapidly growing fleet of old vehicles, poor vehicle maintenance, industrial emissions, construction dust, open waste burning, and even pollution drifting in from neighboring countries add to the problem. Motorcycles, which make up about half of the registered vehicles in Dhaka, emit significant amounts of nitrogen oxides and fine particulates. Large construction projects, like the ongoing Metro Rail, further stir dust and particles into the air.

The economic and social costs of this pollution crisis are immense. Families face mounting medical bills as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases become more common. Children miss school due to illness, limiting their future opportunities. The cost of air pollution to Bangladesh’s economy was estimated at nearly $11 billion in 2019. The human cost, however, cannot be measured in money alone; it is felt in shortened lives and broken families.

There is hope, however, that change is possible. Some brick kiln owners have adopted modern techniques such as zig-zag stacking of bricks and cleaner fuel, reducing energy consumption and harmful emissions by around 20 percent. Hybrid Hoffman kilns consume significantly less coal than traditional kilns. Authorities have started enforcing stricter vehicle emission tests, banning unlicensed kilns, improving air quality monitoring, and promoting public awareness. The government has also launched a national clean air plan that emphasizes regional cooperation, better waste and dust management, and clean energy initiatives. Citizens are encouraged to reduce outdoor activity during high pollution days, use air purifiers indoors, and support sustainable transport options.

Despite these efforts, challenges remain. Enforcement of laws is uneven, and many people still lack awareness of how dangerous the polluted air truly is. The costs of inaction are clear: with nearly five years of life expectancy lost to pollution nationwide and hazardous AQI levels reaching new highs, the city’s future is at stake.

Dhaka’s air is more than discomfort—it’s a silent, systemic killer. Each polluted day translates to shorter lives, sick children, and strained health systems. This is not just an environmental issue; it’s a human and moral one. The dangers are invisible, but the effects are undeniable. Every moment counts: without bold action now, the city we love will choke on its own progress. But with clear policies and public pressure, Dhaka can reclaim its air—and its future.