Salinity Expansion in Coastal Bangladesh: A Threat to Sustainable Development

Salinity Expansion in Coastal Bangladesh: A Threat to Sustainable Development

In recent years, salinity intrusion has become one of the most critical environmental challenges in Bangladesh’s coastal regions. The increase in salt levels in soil and water, especially in districts like Satkhira, Khulna, and Bagerhat, is not just damaging agriculture—it is affecting people’s health, drinking water, livelihoods, and long-term development. What was once a seasonal concern has now turned into a year-round struggle for millions of people living in the southern part of the country.

According to the Soil Resources Development Institute (SRDI), more than 1 million hectares of land in 19 coastal districts are currently affected by salinity. This figure has increased from 0.83 million hectares in 1973 to 1.056 million hectares in 2009, and the affected area continues to grow annually. The World Bank warns that by 2050,saltwater intrusion from the Bay of Bengal could reach up to 100 kilometers inland, increasing the saline-affected zone even further and severely threatening food production, drinking water supply, and biodiversity.

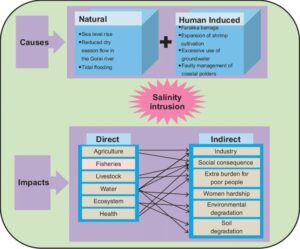

The major driver behind this alarming trend is sea level rise, a direct consequence of global climate change. As ocean levels rise, seawater pushes into freshwater river systems, especially during the dry season when upstream flow from rivers like the Ganges and Padma is limited. This weak river discharge cannot resist the force of the incoming seawater, allowing saline water to move deeper into coastal Zones. Bangladesh’s flat topography and deltaic landscape make it especially vulnerable to this process.

But the problem doesn’t stop at nature alone. Human activities, such as-unplanned shrimp cultivation, the cutting of protective mangrove forests, poor embankment maintenance, and the overuse of groundwater, have all contributed to worsening the salinity crisis. Shrimp farming, while profitable in the short term, often leads to soil and water salinization, making the land unsuitable for other crops. The conversion of 147,000 hectares of land into shrimp farms (as of 2020) has played a major role in spreading salinity further inland.

The impacts of salinity on daily life are far-reaching. Farmers are finding it increasingly difficult to grow traditional crops like rice, wheat, and vegetables. Soil fertility is declining, leading to lower yields and higher costs of production. In some areas, crop production has decreased by up to 30% due to salinity. Livestock are also affected, as saline water is harmful to animals and reduces the availability of grazing land.

Salinity intrusion also brings a public health crisis. The salt content in drinking water has been linked to increased cases of hypertension, skin diseases, and complications during pregnancy among coastal populations, particularly women. A study by the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B) found that women in saline-affected areas are more likely to suffer from high blood pressure during pregnancy, increasing maternal health risks.

Another critical concern is access to freshwater. In many coastal villages, people- especially women and children must walk several kilometers daily just to collect drinkable water. Traditional ponds and tube wells are no longer safe, as the water has become too salty for human consumption. This lack of clean water adds both physical and economic stress to families already struggling to adapt.

From an infrastructure standpoint, salinity damages roads, bridges, irrigation canals, and even concrete structures by accelerating corrosion. This drives up maintenance costs and shortens the lifespan of public infrastructure, putting an additional financial burden on local and national authorities.

The combined effect of these issues creates a cycle of poverty, displacement, and vulnerability. Many families are being forced to migrate to urban slums, leaving behind their homes, land, and communities. This internal migration increases pressure on cities and disrupts local economies and social structures in both rural and urban areas.

“No development is truly sustainable

if it leaves coastal communities behind.”

Despite the growing severity of the problem, there are potential solutions. Some communities have started adopting salt-tolerant rice varieties, promoted by institutions like BRRI (Bangladesh Rice Research Institute). These varieties can survive in saline soil and water conditions, offering hope to farmers who would otherwise abandon their fields. Restoration of mangrove forests, especially in the Sundarbans, is also crucial, as mangroves act as a natural barrier against saline water intrusion and coastal erosion.

Policy support and investment in climate-resilient infrastructure—such as improved embankments, rainwater harvesting systems, and surface water treatment plants—can also reduce dependency on contaminated groundwater. Awareness campaigns, education, and training programs for farmers are essential to promote sustainable practices and prepare communities for future climate risks.

Salinity is more than just a water or soil issue—it is a challenge to people’s dignity, stability, and survival. It affects health, food production, livelihoods, and access to basic services. If we want sustainable development for all of Bangladesh, the growing salt problem in the south cannot be ignored any longer. As the impacts of climate change continue to grow, Bangladesh must prioritize long-term, science-based solutions that protect both people and nature. With the right support and planning, the country can build resilience and secure a future where coastal communities are not just surviving—but thriving.